The Language Behind Science

GIF via Giphy

Scientists, those of us in pursuit of knowledge rather than lining our pockets or seeking our own personal gain, can be relied upon to be the most neutral of the neutral, the pinnacle of unbiased thinking in a world that is so tarnished by opinion and personal point of view. Right?

Mmm, sort of. Science, it turns out, is just as guilty of prejudice in about a thousand ways, from who gets funding to whose findings are more likely to be made public. We could talk all day about this, but since we’re language people, language bias in science is where we’re waxing lyrical today. Come take a look!

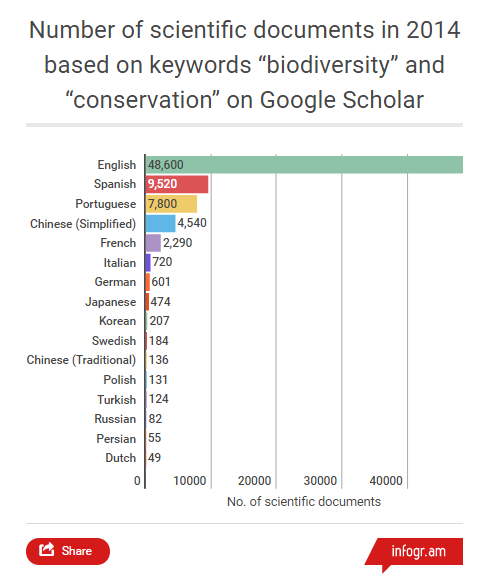

Infographic via SciDevNet

No significant difference

For those who recognise a null hypothesis when they see one, we could propose the idea that there is in fact no difference in the number of papers published in English compared to those in other tongues. Well hold on to your lab coats, because that is about to be proved wrong!

Look over to the right. In this very clear example within the field of biodiversity, the vast majority of papers have been written in English. Authors of the journal PLOS Biology found that out of more than 75,000 documents published in their journal on the subject of biodiversity, around 65% of them were written in English.

Now, if we were going to be truly scientific we would conduct further statistical analysis and look to other science fields to see if the same bias was present in those as well. But we’re wearing our language hats today instead of our safety goggles, so take it as read, that this is seen across the science community.

Cause and effect

So why is English the lingua franca of science as well as just about everything else? Let’s have a little history lesson.

From around the late medieval period up until mid-17th century, the language of choice for science was Latin. Galileo is a classic example of this, publishing his work first in his native Italian and then in Latin for the scientific community to decipher.

By 1900, scientific research was a little more multilingual, written and published in a roughly equal mix of French, German and English, although in some places Latin still had a foothold. Then World War One happened, and that changed, quite literally, everything.

What is it good for (absolutely nothing)

Following the First World War, Belgian, French and British scientists began a boycott of German and Austrian scientists, barring them from attending conferences and publishing in Western journals. Around this time, international organisations governing science became established, with German, which was once the predominant language used for chemistry, effectively being fazed out of their publications.

We also must look to the United States around this time for the change in scientific language use. The United States’ anti-German mentality meant that in 23 states it was criminalised to even use German in everyday conversation, and with less exposure to foreign languages, would-be scientists wrote up their discoveries purely in English. And so by the end of the Second World War, the global scientific community became largely English-centric.

Migration

Still looking at the after effects of the World Wars, scientists migrating from the Soviet Union and parts of Europe following those wars were welcomed in both the UK and America, adding further bias to the language scientific papers were published in. We can also argue that Britain’s colonisation of countries such as the Indian subcontinent has added much to the science language bias, where children grew up learning and using English and therefore went into their adult lives with English as their ‘norm’ for publication.

GIF via Giphy

Findings

So what’s the big deal? Why can’t those papers not written in English just be translated? Well, of course, they can, but that takes time and effort, and if you are researching, pulling together information from multiple sources, it’s likely that you will go to your go-to language to find what you need to know, rather than taking the time to get translations done as well.

But what if this leads to an inaccuracy in your theory? What if key research with the most important data sets is produced solely in Portuguese, and those findings with limited publication would revolutionise scientific understanding but are overlooked? What if including just one paper written in a language besides English in research into, say, cancer, would lead to a new understanding of treatment that could produce a universal cure? What is the argument for English being the lingua franca of science then?

We think we want to know more about language in science; its origins, uses, and also its biases. Join us when we report back from the lab.