Overlooked Languages: Braille

In our quest to find a true, universal language by considering those ones that are often overlooked, this week we are getting all touchy feely and putting the possibilities at your fingertips as well as ours.

We are talking, of course, of Braille.

Forgive us if we get carried away here because we are very, very excited about Braille indeed.

Starting with the history...

...Braille was invented by a fifteen year old boy from France named Louis Braille, who sought to create his own reading and writing system after he'd lost his sight during childhood.

Louis Braille created his system to code for his native French alphabet, and when his second revision of the code was published in 1837 after much success of the first, Braille was announced as the first binary form of writing.

Photo via Wikipedia / Wikipedia

Taking a tiny step back for a moment, Braille has its origins in night writing, a technique developed by Charles Barbier in direct response to Napoleon's demand for a method by which soldiers could communicate with one another in silence at night. This system was a little more complex than Braille, with twelve embossed dots encoding for thirty six different sounds.

Following the rejection by the military of his night writing system, Barbier met with Braille, who instantly, and probably because he literally had first-hand experience, identified two major flaws in Barbier's system. One, with only sounds being represented, the orthography of words could not be sufficiently rendered. And two, it would be virtually impossible for the finger to be able to recognise and differentiate the entire twelve-dot character without moving over it, so in effect, made it impossible to read.

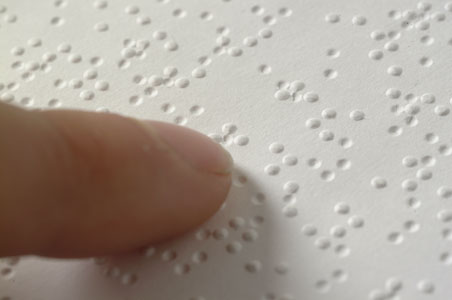

So what exactly is Braille?

Braille is a tactile writing system that is used primarily by those who are blind or visually impaired. Braille characters are depicted as small, rectangular blocks with a series of raised dots that help readers decipher between one character and another. Each character consists of a series of six dots that are raised in sequences so that they may be swept across and read, from left to right, reflecting Braille's Latin alphabet roots.

Braille goes beyond simple letters too: there is Braille for musical notation, and Braille for punctuation, capitalisation, and numbers. Braille can represent mathematical symbols, accents over letters, and in countries who have letters with umlauts in their alphabets, there is Braille for that too. Braille even has its own contractions, so that words can be represented using only optimum space.

Photo via Wikipedia / Wikipedia

We're just going to breathe a little since we've gone giddy with excitement.

In 1878, following the rather rapid translation of the French Braille into probably every language imaginable, the International Congress on Work for the Blind proposed an international Braille standard, and this has produced a script based on phonetic correspondence and transliteration to Latin.

We now have Unified English Braille (UEB), the Braille system adopted by all major English speaking countries, and condenses many former specialised Braille alphabets, such as those for mathematics, science and languages, into one system that is recognised by all.

So has our search for universal language come to an end?

Well, not quite.

Because as widespread as Latin alphabet usage is, it is not the be-all-and-end-all of things. Chinese Braille uses 'traditional' Braille to a point, but characters can then have different readings depending on whether they are placed in an syllable-initial or syllable-final position (and yes, there is a different Braille for both Mandarin and Cantonese, before you ask).

Korea's Braille system is completely novel and separate from the traditional Braille script, and Japanese combines independent vowel dot patterns with modifier consonant dots into an abugida – a single Braille cell that is representative of each Japanese mora.

Learning a new language? Check out our free placement testto see how your level measures up!

Even within those languages using a Latin-based alphabet, there is still variation, because punctuation and characters with different abbreviations and accents to the standard character differ from country to country. And even for those countries whose language is allegedly identical, there is still going to be variations; pants, thongs and chips will forever be different to an American, Australian or British reader, whatever the characters may be spelling out for you.

In 2015, the UK replaced its Standard English Braille (SEB) with UEB, so perhaps, like us, it too is considering the importance of there being one universal language. But even if that were achieved, would we really be happy? There is something so satisfying and exotic about reading a piece of text full of little clues in the form of accents and umlauts, telling us that the story conjured up on the page is of far off, foreign lands we might never get to experience for ourselves. That might just be the traveller in us romanticising things though; we're not sure.

But besides all that, and possibly more importantly: Braille isn't even really recognised as a language, more a code in which all languages can be written and read.

Ambassadors for inclusion

At the Grammys earlier this year, Stevie Wonder took a moment before presenting an award, to raise awareness of the importance of accessibility for all of those with a disability. Despite the widespread use of Braille throughout the world, total availability still hasn't been achieved; you only have to look on Goodreads to see just how few works are actually translated.

Things are changing for the better though: banknotes in Canada, Mexico, India, Israel, Russia and Switzerland have a series of raised symbols allowing those who are blind or visually impaired to be able to distinguish between the different values. In the UK it is a legal requirement that all medicines are labelled both in written English and in Braille. In America, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 requires that all building signage is also displayed in Braille, and in India, under The Right to Information Act, many parliament acts have been published in Braille.

We are on the up, then.

Photo via Wikimedia / Wikimedia

Can you imagine a world without the incredible works of Helen Keller, the beautiful music of Ray Charles, or the philosophies of Homer? Each of these people were blind, or visually impaired; that never stopped them achieving great things, and imagine how many more people can go on to achieve equal greatness if they have the tools of the trade to do so?

But Braille isn't even a language...

Before we get soap-boxy, let's look at the facts: Braille does tick a lot of language boxes. It is translatable, has an alphabet, rules, and conventions to follow should you want to understand it. It can be used to share information and pass on instructions, but most importantly, it is a form of communication, like any other available language.

So to us, Braille is a language, an important one that needs much more recognition.

We've come down now from our emotional high of language discovery, so we'll leave you with this thought: why are languages such as sign language and Braille so often not listed amongst the options of languages that you can or can't speak? Is it prejudice, oversight, or merely a huge work in progress?

Next week we'll be attempting to tie up any loose ends from this look at these important, overlooked languages; we look forward to sharing our thoughts with you then!