“Inclusive Writing” for Gender-Based Languages

Jumping off of the last article discussing possible inherent sexism embedded within a language, inclusive writing in terms of gender should really not be the new trend in writing that it seems to be. However, for some of us, it is. With that in mind, how does attempting to writing more inclusively work when you are writing in a gender-based language? How do you embrace change without offending the language purists and get the balance right? Here's a look at how inclusive writing is working out—or not—in French and Spanish.

French

We already know that French-speakers are incredibly protective of their language and are dead against the polluting of their tongue with anything that isn't French (predominantly English, but other languages too). So we would already expect it to be difficult for some Francophones to adjust to the idea of gender neutrality in the language, especially with such strict policing of masculinity or femininity in articles and endings.

Table of Contents

Photo via MaxPixel

Inclusive writing, or écriture inclusive, is an attempt to strike the balance between what we already have—the French language—and what we're trying to do—include everyone. The first step has been to go against masculine grammar constructs. Le juge for example is judge but the le 'makes' it masculine. Some are starting to refer to female judges as la juge defying grammar police everywhere!

A second grammar faux pas is the alteration of endings. The addition of a solitary e to a noun to 'make' it feminine, auteure in place of auteur for author as an example. These small changes have been adopted by many in everyday language yet there are also many French who prefer more traditional nouns.

A step too far?

To make French more inclusive is the proposal of the middot, a punctuation point that does away with the need for either male or female and allows for both. Citizens (citoyens) becomes citoyen·ne·s, readers (lecteurs) lecteur·rice·s, and so on. Relatively straightforward and not too much to adjust to, even if it doesn't really offer a solution for spoken French.

Of course, there was an outrage, the Académie française declaring the move a "mortal danger" to the language, and in November 2017 the then Prime Minister Édouard Philippe put a ban on this gender neutral language in all official government texts.

Spanish

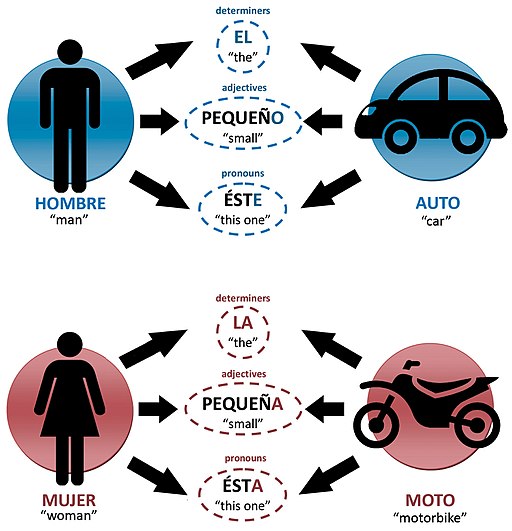

Spanish has the same difficulty as French with nouns being only either feminine or masculine, and the rule of masculine over feminine forms used for mixed sex groups.

Numerous approaches are being tried to get around this and include both sexes. The first, like French, seems to only help for the written form of the language, and is an adaptation adopted more in Latin America than in Spain. In place of the a or o in a word that identifies it as masculine or feminine is the suggestion of the @ sign. Trabajador@s would therefore mean workers with no indication if they are male, female, or a mixture of both.

Photo via Wikimedia

Learning a new language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

A step better here in terms of wondering how best to pronounce that @ sign is the letter X added to the end of the word. Latinx, pronounced la-teen-ex, refers to those of Latin American culture or identity, in place of Latino, Latina and even Latin@.

Perhaps the easiest in an attempt to keep everyone happy is the adoption of saying both forms of a word. For instance, in greeting everyone you might say todos y todas in place of just todos.

Getting critical

The Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) does not approve of any of this lenguaje incluyente. They argue that the masculine form is already gender neutral to include everyone, and say that using both versions of words means causing more of a divide. The RAE even suggest that women are already grammatically included in masculinised forms of words; would the reverse be argued if we were to adopt, say, cuidadanas to mean all citizens, instead of just female ones?

Photo via Flickr

No right answers

Language is always such a contentious subject, torn between two views of clinging vice-like to the past and adopting every neologism for the five seconds it becomes popular before moving on to the next one. And of course there are shades of grey between those two viewpoints, but for something as important as inclusivity, there has to be a happy medium for us all to agree on. Suggestions, anyone?