The Most Confusing Consonants in Europe

When you are learning a new language or even just travelling to a new country, you can find yourself wrapping your lips around tongue twisters that you never even expected. Letters are not necessarily pronounced the same abroad.

Adventures in paella

To illustrate that point, take the humble paella.

To an English speaker who has not had the disdain of a Spanish waiter glaring at your truly awful attempt at the word paella, please attempt to understand our pain.

In England, we say pie-el-a but in Spain, the two lls next to each other transform into another sound entirely and paella becomes pie-ey-ya. Which then of course you say to your family when you go home and are frowned upon for being pretentious. Which you’re not.

This episode was brought to you by the (double) letter l

Continuing with the theme of the double ll for a moment and our brief stop in Spain, imagine our confusion when we see the word Nolla. In England we would say nol-a, but if you’ve ever had a foray into the beauty of the Finnish language, you know firstly that Nolla means zero, and secondly that it is pronounced noll-la, because the Finnish language uses gemination. In Spain Nolla is a surname and pronounced more like noy-ya.

It is very confusing out there in consonant land.

So, imagine our joy and vindication when we came across this Independent article that details the way in which consonants change around Europe. Here’s a whistle stop tour of the travelling consonants.

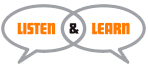

J

Table of Contents

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

J is a tricky little letter that likes to confuse language learners. Take the English word jam, which is confiture in French and mermelada in Spanish. This innocent-looking word is often mistaken for ham in these countries because in French this is jambon, in Spanish jamon, and the mix up over letters could produce a very interesting accompaniment to your croissants.

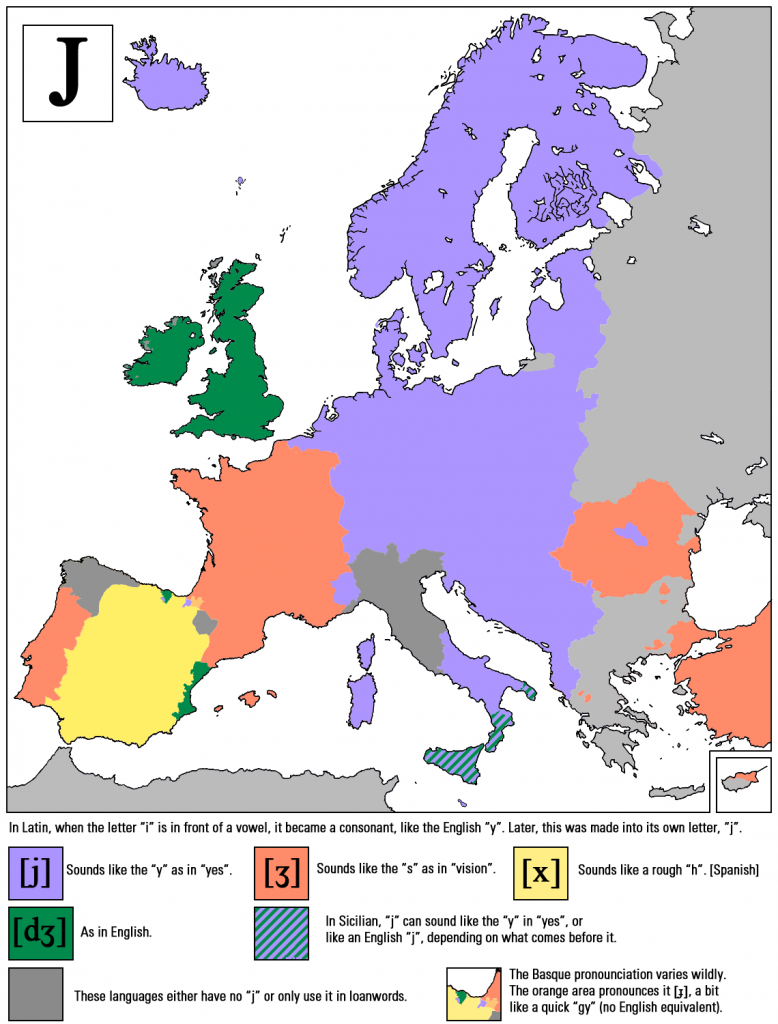

H

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

It is interesting how pronunciation of the letter h can often depict where you are from in the UK. If you are constantly dropping them from words like house and her you are more likely to be from London rather than Edinburgh, for example. However, it is one of the friendlier letters to work with when learning a language because so often it sounds as we expect it to – in words like haus from German for example (house).

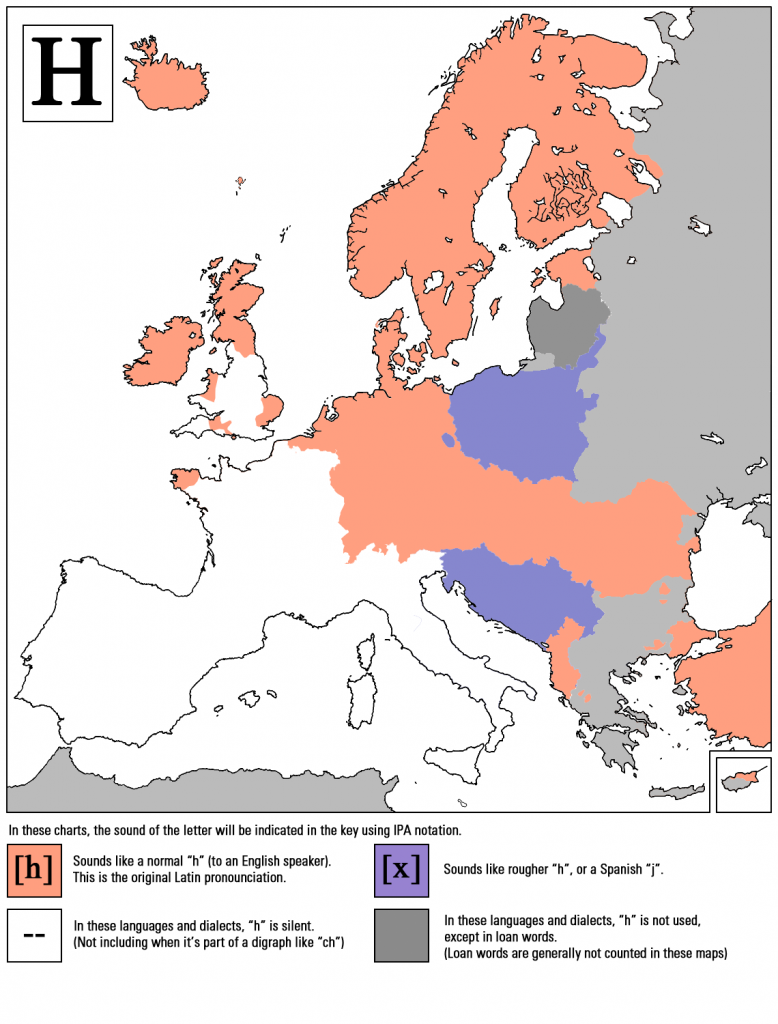

X

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

X is a nice little letter to play with when learning a language, simply because as you can see from the maps, it either doesn’t change much or doesn’t really exist aside from in loanwords!

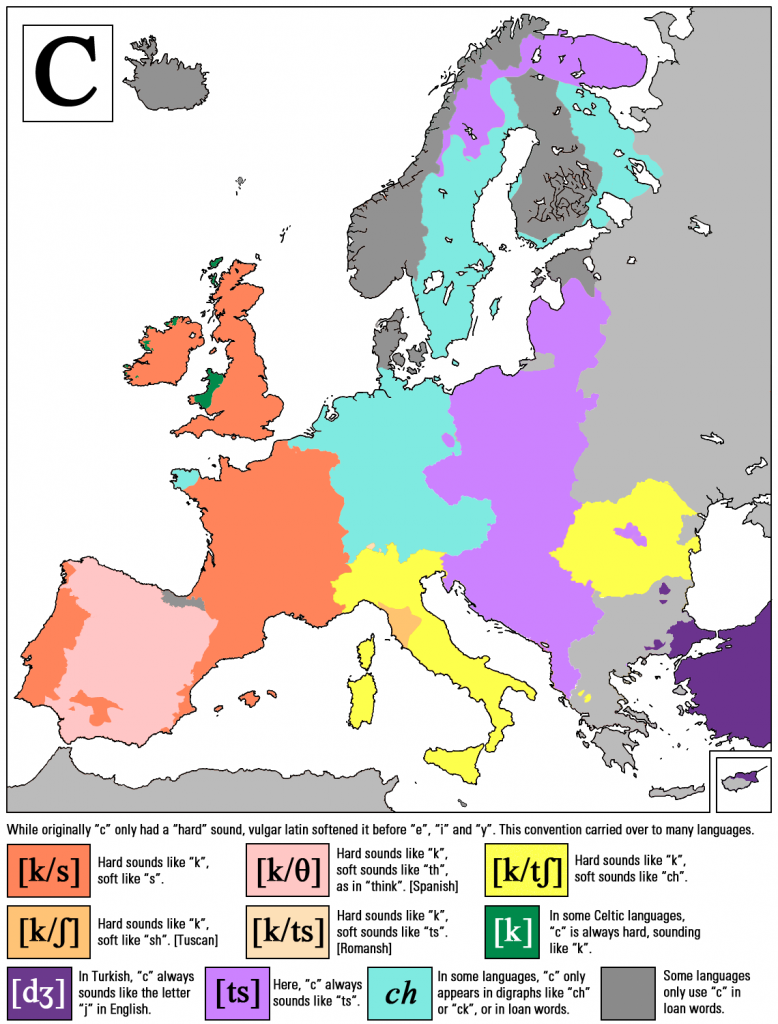

C

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

C is a multipurpose letter at the best of times, even within the same language. There is some comfort in seeing it (mis)behave similarly for other languages too. Take for example the English word shoes in Hungarian – cipő – which is pronounced tsi-per.

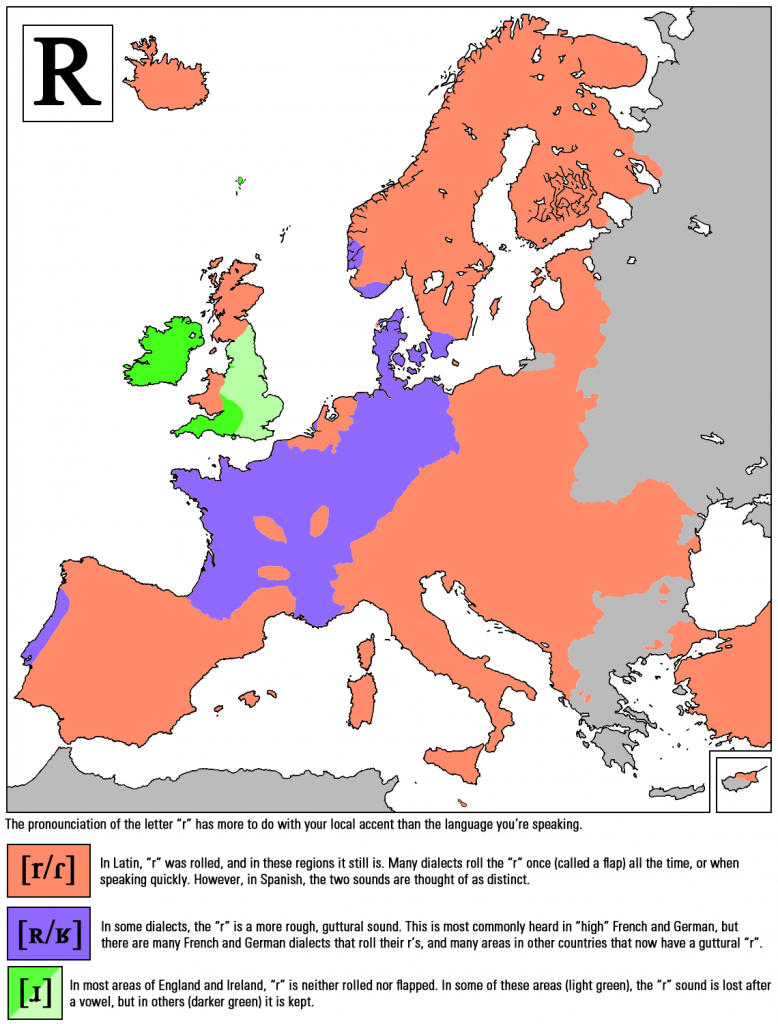

R

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

It isn’t rhotacism that makes saying the letter r differently difficult abroad, it is the way our mouths are formed pronouncing words from an early age. An r in British English can either be ‘hard’ as in road or disappear in words like where. But in a vast part of Europe the r is rolled, and this can be incredibly difficult when learning a language. The word for dog in Spanish – perro – is one that can make even the hardiest of learners blush with effort.

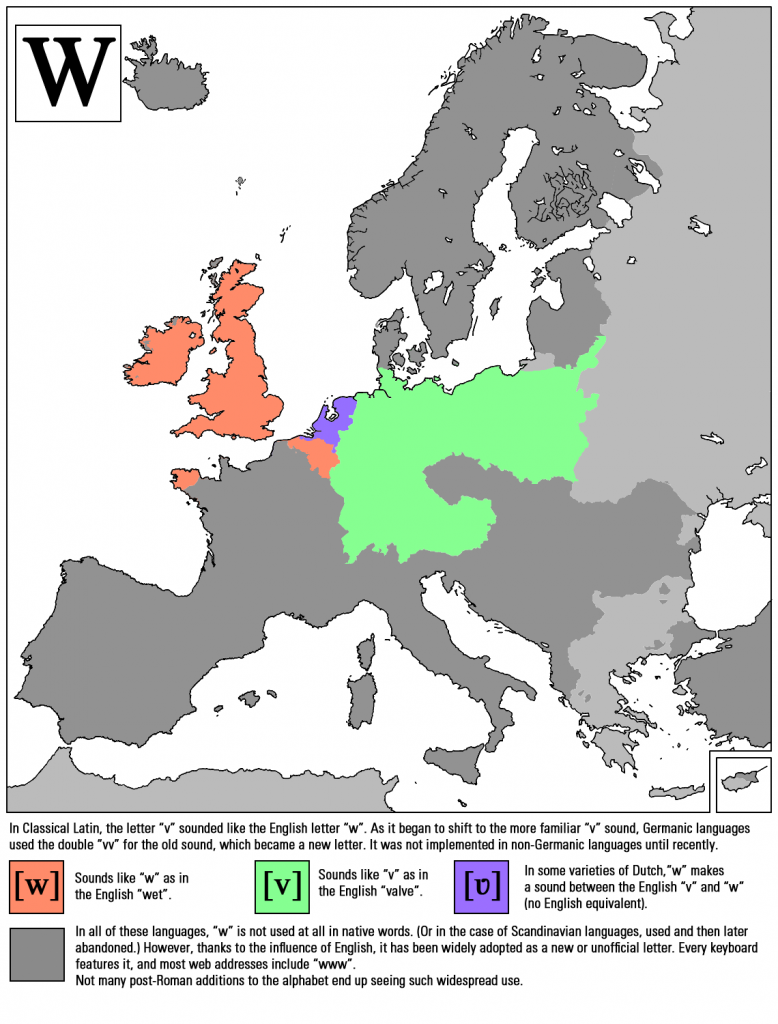

W

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

W is a good friend of the letter x because it is so rarely used across Europe. Where it is used, it is either pronounced like the English write – rite – or the German wie (as) – vee. So there thankfully is not much room for error.

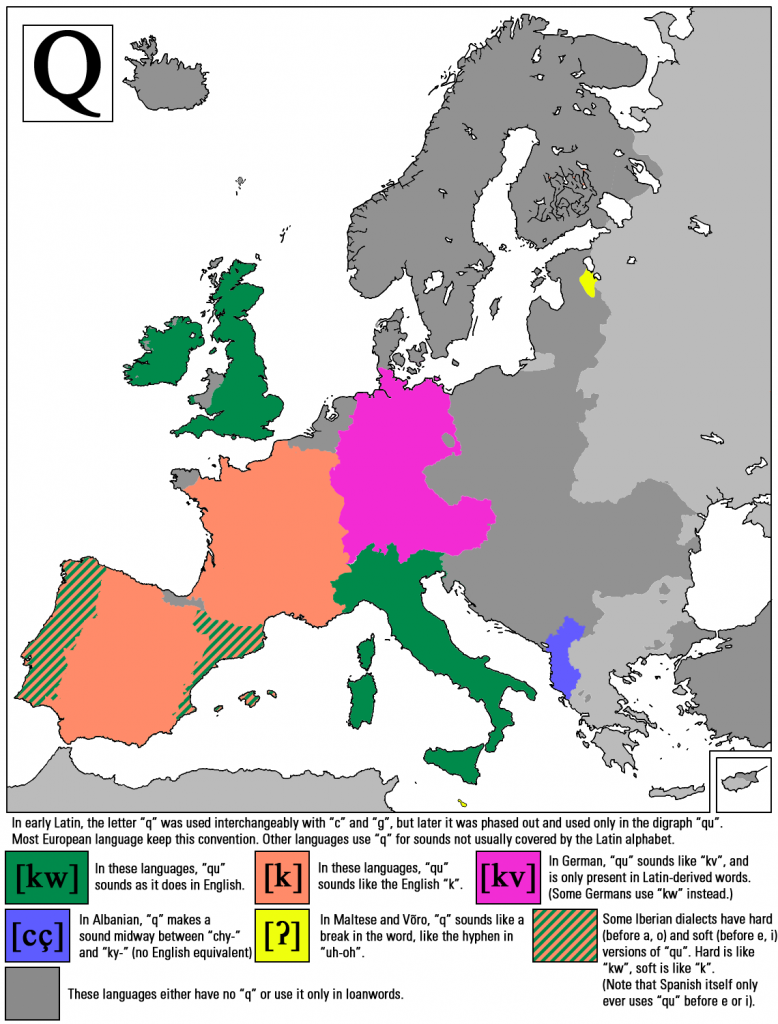

Q

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

As a letter with such a high scrabble score, the letter q certainly knows how to twist a tongue. Since it is in constant companionship with u the pronunciation, depending on where you are in Europe, will be heard either as kw or kv. In England it is always kw – as in queen – but in German it can be both; quoten (rates) can be pronounced both k-vote-n or k-wote-n. In Spain is an exception to this since their q sounds like a k, as demonstrated in queso (cheese), pronounced kes-o.

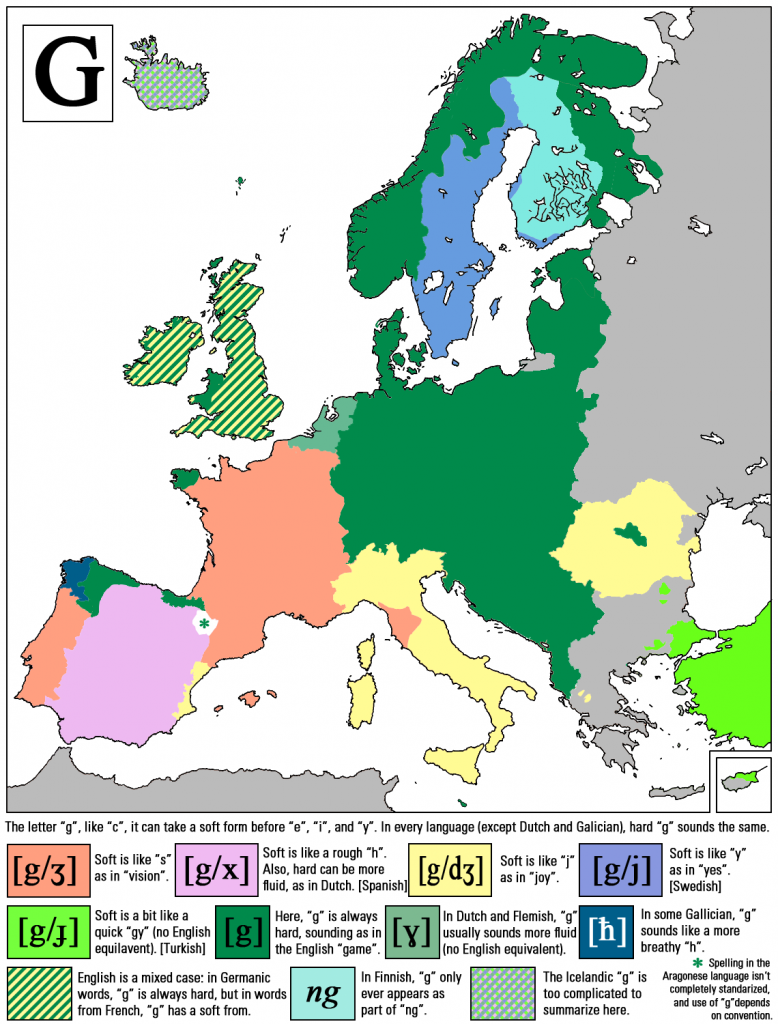

G

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

G in English already masquerades as different sounds, from the hard sound of goat to the softer one of Germany. This is also true in other languages, for instance in Hungarian. Again, the sound can be hard like in gabona (cereal) or soft in gyakorlás (exercise). This is more to do with which root the language originates from: more German-rooted words are hard – gut (good, German) whereas those that are more Latin-rooted are always soft – gelato (ice cream, Italian).

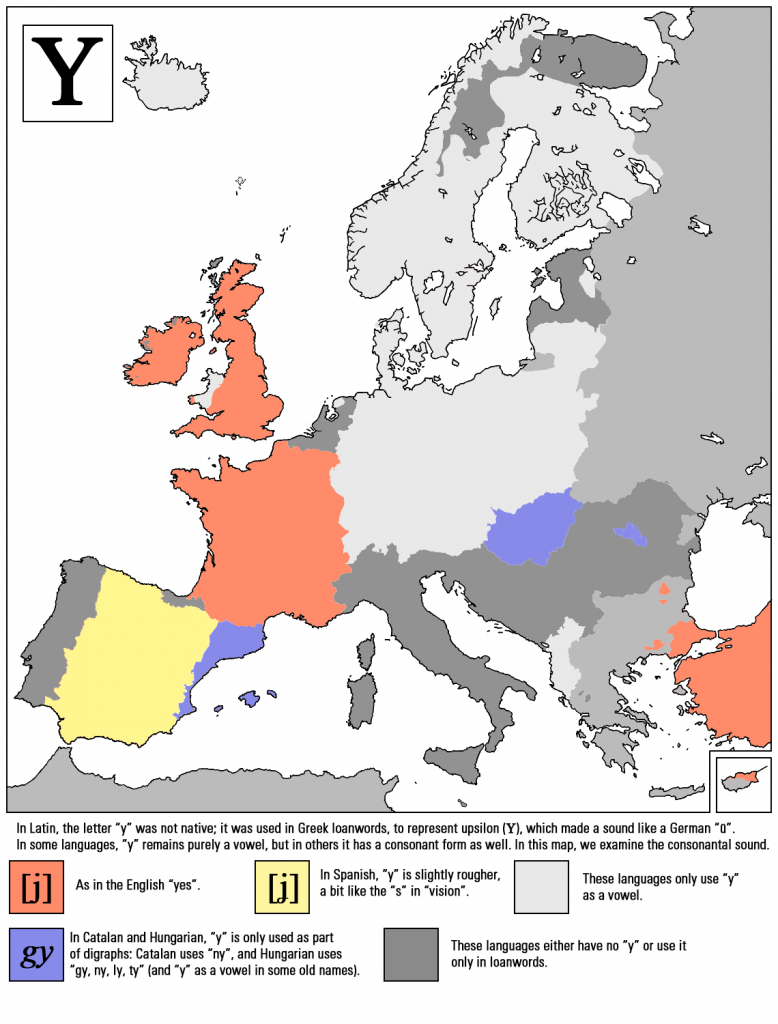

Y

All images courtesy of Alexander Young via The Independent

Y is our final letter that has limited use throughout Europe. It most often sounds like the English yes but this can be a little rougher in Spanish with words like yo (I). In Hungarian the y only ever comes out to play when the letters g, l, t and n need chaperoning, and serves to soften their sound – but not necessarily their pronunciation – like in gyakorlatiasság (practicality).

So there we have it. You weren’t imagining it: letters do play differently when they are on holiday too!

Your own consonant adventure

If you are planning your summer holidays in Europe and this adventure in consonants has inspired you to get some basic vocabulary before your travels, why not contact us and see what courses we have on offer in your area!