Esperanto vs Fictional ConLang: Why is Fiction Winning?

Table of Contents

Photo by Phil Plait/Flickr

TlhIngan Hol Dajatlh'a'?

There’s a reasonable chance that most people looking at that will see not a sentence but the result of a terrible mid-air crash between a dictionary and a blender. However, an increasing number of people across the globe will recognise that as meaning ‘Do you speak Klingon?’ – a language popular among a select group of Star Trek fans, and an example of a ‘ConLang’.

A ConLang is a ‘constructed language’, namely one which has been consciously devised for human communication rather than having developed naturally. There are various examples from the worlds of literature, music and popular culture, in addition to the more formerly constructed languages best epitomised by Esperanto, and it is in considering the language created by linguist Ludwik Zamenhof in 1887 that we notice an interesting facet of language learning in the 21st century: Klingon and the like are enjoying a golden age, according to an article in The Guardian, at the expense of Esperanto – but why could this be?

Here we examine a few reasons why the more unlikely ConLangs are booming in a sphere when Esperanto could be expected to flourish.

Associating a language with a culture

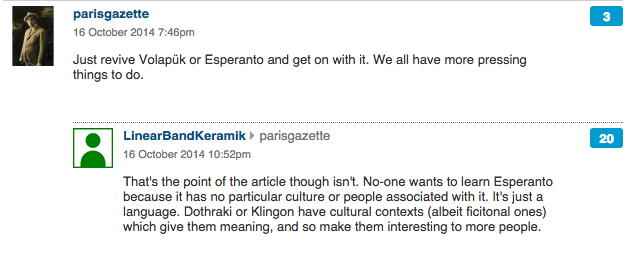

An interesting comment on Guardian article above highlights one reason people are more keen to learn less formal ConLangs over more established ones:

When people come to learn a new language they automatically place it within the context of a culture or society. When someone chooses to learn German afresh, they do so with the thought of speaking German to German people, or understanding German media, or travelling to Germany and being able to hold their own in restaurants, bars and while getting around.

Admittedly you’re unlikely to be able to visit the Klingon home world any time soon to be able to try out that particular ConLang on the natives, nor more likely to find an unexpected route to Middle Earth to practice your Quenya or Sindarin. Nevertheless you can image the Klingons as a race, like the Elves in J.R.R.Tolkien’s fictional world. It is easy to place a language such as these within a cultural bracket with a little imagination, but doing the same with a language like Esperanto is not as simple.

Esperanto was created as a way to foster harmony between people from different countries, but for that very reason it’s impossible to ally it with one cultural group. Its speakers are from every country and walk of life, and though there are Esperanto conferences and societies it’s still too hard to picture yourself as a speaker of Esperanto, sitting outside a coffee shop in the sun listening to all the other Esperanto conversations nearby. Without a culture to twin it with, Esperanto and other formal ConLangs are like coats without hooks to hang them on.

Placing yourself in a fictional setting

Everybody wants to be an actor, right? Well not necessarily – some of us are terrified by the idea of appearing in front of a baying audience who will judge failure in the harshest terms – but it’s fun to imagine oneself on a TV show, holding our own against, to use the obvious example, massive, angry aliens with odd-looking foreheads. You’ll probably want to be fluent though; those bat'leths look sharp (giant Klingon swords, to the uninitiated).

There’s something immediate and enjoyable about imagining yourself part of an alien race who speaks a language that you, as a human in the real world, can actually learn. It is quite the opposite of picturing yourself as a speaker of Esperanto, which has no reference in fiction whatsoever and allies itself more easily with earnest, staid conversation about, well, probably Esperanto.

The rise of geek culture

Unless you’ve been locked in a cellar for the past few years you will have noticed that what is termed ‘geek culture’ has become hugely popularised recently. Video games are a massive business, superhero movies dominate cinemas and technology is at the forefront of everyone’s lives much more than ever before.

A direct result of this is that things which used to be marginalised as ‘not cool enough’ for the general populace are now perfectly at ease in the mainstream. Though it would be a stretch to say it’s fashionable to know how to speak Klingon, the simple fact that there are more people willing to openly admit they love Star Trek (not least thanks to the movie franchise’s successful reboot) means that knowing how to say a few phrases in Klingon can provide you with an entertaining party trick.

The same can’t really be said of Esperanto – if anything, with geek culture so popular you might now be seen as less cool if you choose a constructed language rarely heard in games, movies, or other 21st century media.

Formal ConLangs versus natural languages

Perhaps the biggest issue for Esperanto and other more formal constructed languages is the same problem it has faced since inception: while in theory it is meant to bring people of different nations together, (with learning a natural language now easier than ever) it’s far simpler if one of the two participants in a conversation already knows it fluently. Why would two people from two nations learn Esperanto rather than one learn the other’s language? The natural language will ultimately be more useful in life, for example in being able to work with overseas business clients or moving to another country.

And if you therefore decide to learn a new language but decide to go for a constructed language rather than a natural one, the other reasons above are more likely to push you towards a fun, alien tongue than a formal one such as Esperanto. There will always be a place for a language that can cross borders, but in an increasingly globalised world there’s no guarantee people will choose to say je via sano* as they raise a glass when they could say ReH Hlvje'lljDaq 'lwghargh Datu'jaj**.

* ‘To your health’ in Esperanto.

** ‘May you always find a bloodworm in your glass’ in Klingon. Might be better to stick with real languages after all!